It hasn't, so far, got much media traction, but the World Bank released an extraordinary piece of news yesterday.

By the end of this year, for the first time in history, less than 10 per cent of the world's population will be living in extreme poverty.

And that's using a higher income figure than the UN's, which at $1.25 is the standard benchmark: the World Bank is using $1.90.

In 1990, the figure was 37.1 per cent, or 1,959 million people. In 2012 it was 12.8 per cent and it's set to fall to 9.6 per cent by the end of 2015.

There's nothing bad about these numbers, except the speed at which they are decreasing: it's quite dramatically fast, but if you really think about what it means to live on that little, not fast enough.

Nevertheless, the progress has been remarkable. It's been driven largely by macro-economics, huge growth in China and to a lesser extent India in particular. The size of these countries means that in absolute terms, the numbers affected have radically altered the poverty graph. Industrialisation has led to millions being set free from subsistence farming and turned into wage-earners.

Does this mean that the time is coming when anti-poverty campaigners can put their feet up with the sense of a job well done? Not any time soon, unfortunately.

For one thing, there's the unevenness of the reduction. In sub-Saharan Africa, extreme poverty will still be 35 per cent at the end of the year. This is a fall from 46.2 per cent in 2012, but it's still far too high – and it means that half of the world's extreme poor will be found there.

The World Bank also warns that what it calls "non-income disparities" – like limited access to quality education and health services – are "a bottleneck to poverty reduction and shared prosperity". Furthermore issues around climate change and environmental degradation are still major challenges: "In sum, while development progress was impressive, it has been uneven and a large unfinished agenda remains."

It identifies three key challenges: the depth of remaining poverty, the unevenness in shared prosperity, and the persistent disparities in non-income dimensions of development. It says that policy-makers have to concentrate on the poorest of the poor, targeting income growth among the bottom 40 per cent of the population – and it warns that growth after the financial crash might not continue at the levels experienced before it. And it warns that inequality of opportunity "transmits poverty across generations and erodes the pace and sustainability of progress". Translated, this means that if countries are corrupt, highly stratified and don't allow their best and brightest the educational and entrepreneurial opportunities they need to create wealth, they won't get richer – and might even regress.

The anti-poverty cause is dear to Christian hearts. The Make Poverty History campaign of 2005 saw thousands of Christians sign up to its ideals. Extreme poverty is seen as an affront to God's design for human flourishing. Its decline can only be welcomed.

However, campaigners also want to sound a note of caution. The Millennium Development Goals (MDG) have just been superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), agreed last week by the United Nations. Their aim is to eliminate hunger, reduce inequality, promote shared economic growth, and "end poverty in all its forms everywhere" by 2030. In World Bank terms, this means extreme poverty – measured not just by the $1.90 a day income standard but by a broader definition that takes in "non-income deprivations" – falling to less than three per cent.

Is it achievable? According to Helen Dennis, adviser on poverty and inequality for Christian Aid, it is – but she has reservations. She welcomes the progress that's been made but stresses that $1.90 a day is by almost any standard a barely minimal income; she cites a Christian Aid partner who remarked how insulting it was to imply that someone with an income of, say, $3 a day was somehow not poor.

She also points out that income is only one element of poverty. If people experience inequality, social exclusion and various kinds of disadvantage, the job is not done.

Furthermore, there are countries were poverty is particularly intractable, and this is the result of political choices as well as naked economics. Countries that rely on "extractive industries" – mining, gas and oil – tend to have more poor people in proportion to their GDP because these are valuable but not labour-intensive industries, so the profits are concentrated in the hands of fewer people. So eradicating poverty involves much more than just increasing the overall wealth of a country: it means deliberately choosing policies that redistribute wealth to poor people and give them a stake in how it is used.

The World Bank's mid-term target is to reduce extreme poverty to nine per cent by 2020 – on the face of it a very modest goal. However, it's cautious. In its report it describes the three per cent final target as "ambitious" and "aspirational", warning that 'business as usual' policies are unlikely to get there: "Unless extra efforts are made to ensure economic, environmental and social sustainability, the pace of poverty decline associated with a given rate of economic growth can be expected, at some point, to diminish markedly and possibly even reverse."

So: better healthcare, clean water, better education, social insurance – it's all part of ensuring that poverty really does reduce. And the low-hanging fruit has already gone. What seems clear is that what's left are the far less tractable problems which will require real changes of mind among ruling elites, political liberalisation and a genuine desire for change.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals are ambitious. They include No Poverty, Zero Hunger, Quality Education, Reduced Inequality and Clean Water. As Helen Dennis says: "The challenge is to see world leaders make good on their promises, commit resources and take the difficult decisions about redistribution."

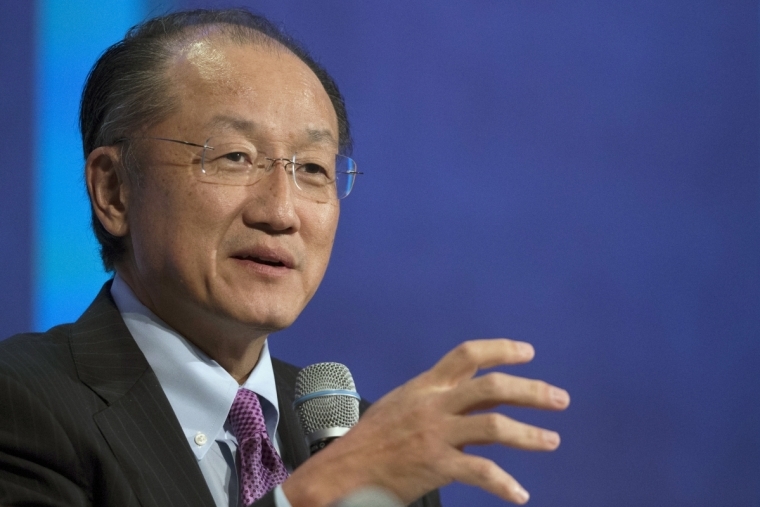

It's easy to be discouraged by the scale of the world's problems. However, the lesson of the last quarter-century is that change is possible. As World Bank President Jim Yong Kim said: "We are the first generation in human history that can end extreme poverty."