An old man and his treasures

He sat propped-up in a wicker chair gazing out of the window. With feet wrapped in tartan slippers in coordination with the navy gown tied securely around his waist. A chipped teacup held a lukewarm beverage unsteadily in the faded skin of his well-worn hand. His blue eyes faded grey by cataracts, framed by lines smiling from the yonder years of youth.

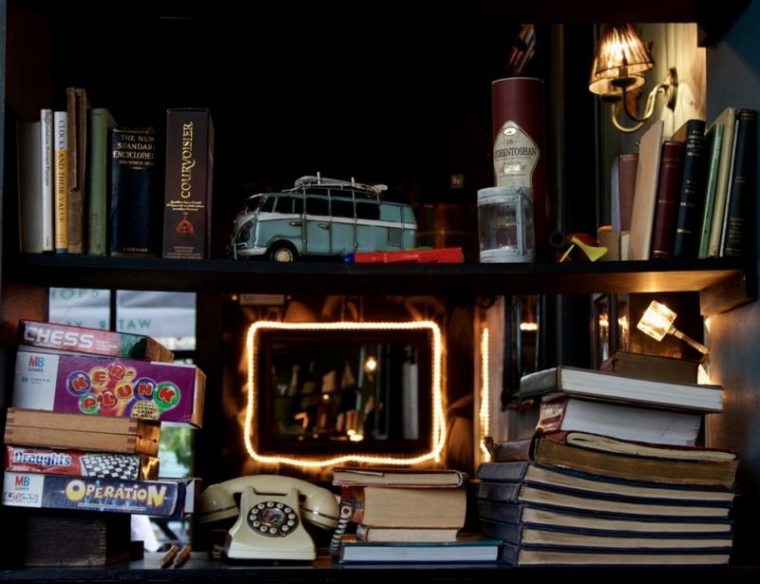

On the first appearance, he was being suffocated by a random museum of archaic items. However, on closer inspection, this collection of miscellaneous treasures told a story. His story.

Photographs of his sweetheart and family – loved ones he hadn’t seen in years. Collections of books, porcelain figurines and model cars firmly stood their place in the dark mahogany of wooden cabinets. A light coat of mothballs and dust fragranced the air.

His home, both his fortress and prison.

Re-defining worth

Perhaps it is a morbid declaration, but the truth is – we are all going to die. As we encroach closer towards our ultimate end date, we are prompted to consider the concept of worth. The worth of life, the worth of possessions and the value we perceive others attribute to these.

In his book, Secondhand: Travels in the new global garage sale, 2019, Adam Minter, delves into the fascinating world of secondhand items and the very human process of downsizing in retirement. In an interview with EconTalk host Russ Roberts, Minter further discusses the professional business of the cleanout industry.

Minter defines the cleanout industry as a group of professionals who help older adults downsize before moving into retirement. Retirees come face-to-face with the stark reality that their kids don’t want their old stuff. Hence professional cleanout consultants counsel others through the traumatic downsizing process.

Death cleaning

The Marie-Kondo method has been joined with the on-trend Scandinavian model of Swedish death cleaning. Bringing with it the new promises of not only sparking joy but also ensuring that our loved ones will regard us with eternal affection.

Swedish death cleaning is a term used to embody the process of removing unnecessary things from one’s environment in the preparation of death. Perhaps this final frontier of cleaning resounds with a morbid tone. However, it poses the question – how did we come to this point?

Why, out of sheer necessity, do we need to downsize, downsize some more, and then death clean?

And finally, why should we wait until retirement before we begin the process of re-defining an objects’ worth?

Our process of defining an objects’ worth is highly dynamic and individualised. Perhaps, it is sentimental, useful, or simply beautiful. Regardless, we risk the potential of being stuffocated when we tightly hold onto our material possessions.

Additionally, our culture has shifted from allowing transitional periods in life to naturally prompt us to evaluate relationships, into covertly compelling us to clean out our wardrobe. We have trivialised worth – narrowing it down into determining if it sparks joy?

Furthermore, the greatest danger we may face is, in fact, the loss of our social conscious. We have begun to value our possessions more than the person who made them. Essentially, we assign more value to things over people.

Fostering a social conscious

The fact is this. In the Western world, we have too much stuff and we care too little about where it came from.

UNICEF states that an estimated 260 million children are currently engaged in child labour. According to the International Labour Organisation, many of these children – approximately 170 million of them - work to make textiles and garments to appease the demand of Western consumers.

In Proverbs 3, verse 27-28, we are implored to not withhold doing what we know to be good when we are able to act.

“Do not withhold good from those who deserve it; when it is in your power to act. Do not say to your neighbour, “Come back later; I’ll give it to you tomorrow” – when you have it with you now (Proverbs 3, verse 27-28).”

As accomplices to unethical global trade, we continue to excuse our inaction as ignorant passivity. However, we aren’t ignorant - this isn’t breaking news to us – is it?

Although we know these statistics, we continue to choose to deprive children, and others, of their fundamental human rights in exchange for our prized collection of treasures.

Home – fortress and prison

Choosing to value things over people isn’t helpful for us either.

Our clutter full fortress forms a protective barrier against social engagement. We question whether we have the correct gear list for entertaining a social gathering – large dining area, appropriate indoor/outdoor flow, large TV, modern furniture, and even a pool. We excuse our ability to be hospitable because we do not fit social media’s portrayal of the perfect host or domestic goddess. Yet, we wonder why we are lonely.

We live imprisoned by homes stuffed full of things we hold with fierce affection. Until the time comes when we deem these objects no longer worthy of our adoration, hence prompting their careless discard. Yet, we wonder why we feel burdened.

Our home has become both our fortress and prison.

Kiwi-born with British roots, Jessica Gardiner drinks tea religiously while her dinner table discussions reverberate between the sovereignty of God, global politics, and the public health system. Having experienced churches from conservative to everything but, Jessica writes out a desire for Christian orthodoxy and biblical literacy in her generation. Jessica is married to fellow young writer Blake Gardiner.