We’ve become familiar with words such as ‘lockdown’, ‘social distancing’, ‘self-isolation’ and ‘quarantine’ in these days of Covid-19. But plagues (and viruses) are nothing new in human history. How we respond to them may have changed, largely due to modern medicine and a better understanding, but the notion of quarantine and isolation is not new.

But nothing done today can match the response of a small English village, several hundred years ago, when people responded to the spread of the plague in their midst.

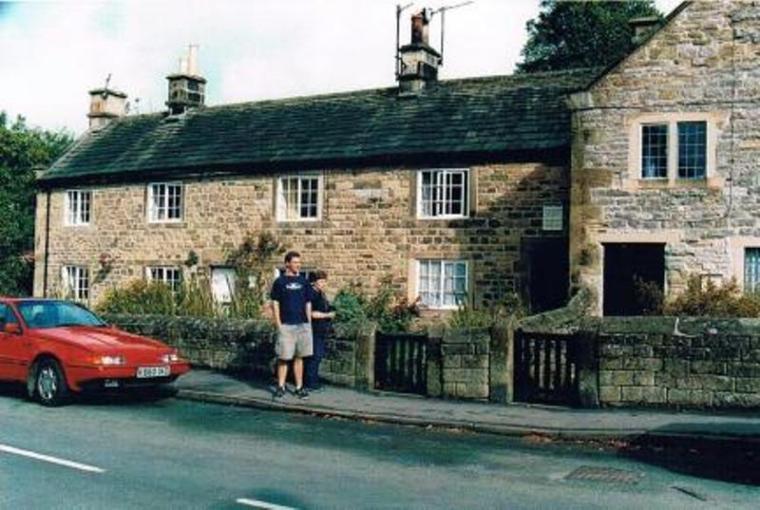

We visited this little village with our son, during his gap year, after we had been alerted to the story by an English friend in New Zealand. On the surface the village was just like many other small English villages; quiet and quaint, with stone cottages, a large church, a pub and store, and with a village green in its midst. It didn’t take long to find out more.

It all began with one person…

In 1665 a tailor in the small village of Eyam in Derbyshire ordered a bolt of cloth from London. There the plague was spreading like wildfire, but it hadn’t gone much beyond the city. Some fleas carrying disease came with the tailor’s order, and soon villagers started to fall sick and die.

William Mompesson, the local vicar, discussed the matter with his predecessor, also living in the village. Rather than having villagers flee to surrounding areas, taking the plague with them, they decided the village should isolate itself to contain the plague. The villagers were reluctantly persuaded to take up the challenge to self-quarantine, and arrangements were made for food to be brought to the village outskirts in exchange for money. The coins were left in vinegar, the only way they knew to disinfect them.

The cost was heavy. Over a period of 14 months numbers of people became ill and died. The vicar’s wife, Catherine Mompesson, who had refused to leave the village in order to care for the sick and to support her husband, was one of the victims.

One villager, Elizabeth Hancock, lost all her five children and her husband in the space of eight days. She dragged each body to a nearby field, dug their graves and buried each one herself. Those watching her from a nearby village were too scared to help her.

In all, 260 people from 76 families died. But the quarantine cordon worked. It is estimated that thousands of people in nearby centres such as Sheffield and Manchester were spared. The village has now become known as the one that sacrificed itself for a greater good.

Eyam today

We walked the stone streets, and read the names of the inhabitants who died, listed on the walls of the ‘Plague Cottages.’ There are descendants of the survivors of that terrible time who still live in the village, and their research can be found in a museum that helps visitors understand and honour those who suffered so much.

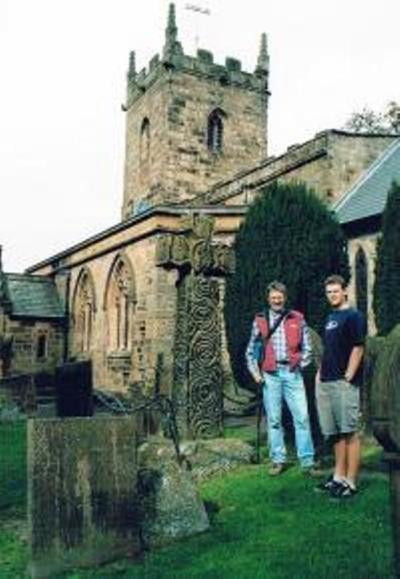

The museum was closed, but we visited the church, and its graveyard with many ‘plague graves.’ (During the plague, worshippers met in a nearby field and practiced ‘social distancing’ during services, gathering as families, but separate from each other.) The church has continued its worship during the 350 years since the plague struck, and though it recognises and remembers its plague history, it doesn’t live in the past, but continues to uphold the same faith that inspired William Mompesson.

As he encouraged his parishioners to be prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice, a faith that includes Jesus’s words: ‘Greater love has no one than this, that he/she lays down their lives for their friends,” so we too have been challenged in these days of Covid-19 to self-isolate for the sake of others, as well as ourselves, and to the extent that we have done so as a community, have fulfilled the words of Jesus.

Remembering Eyam, reminds us too of the cost of Christian service then – and also now. During 2020 the suffering world-wide has been very great. Not only have hundreds of thousands of lives been lost, but sometimes health workers too have died – just as Catherine Mompesson did, because she committed herself to the care of those who were suffering.

Pray for those putting their lives on the line as they care for others.

Liz Hay rejoices in living in a beautiful part of God’s creation in a high country mountain basin; and she also rejoices in hearing stories of God at work in people’s lives. One of her favourite activities is reading fascinating biographies that illustrate the wonderful ways God works uniquely with each person.